Understanding “The Fly” by Katherine Mansfield

Introduction

In this post, we’re going to explore one of the most haunting and deceptively simple short stories in English literature – Katherine Mansfield’s “The Fly,” written in 1922.

Now, before you think this is just a story about an insect, let me tell you – this little tale packs more emotional punch than many novels twice its length. It’s one of those stories that seems straightforward on the surface, but the more you think about it, the more layers you discover. Kind of like when you’re watching a really good psychological thriller – you think you know what’s happening, but then the ending hits you and you realize there was so much more going on beneath the surface.

The text and audio of “The Fly” is available here.

About Katherine Mansfield (Brief Context)

Katherine Mansfield was a New Zealand writer who lived from 1888 to 1923 – a tragically short life, but she left behind some of the most powerful short stories in the English language. She died of tuberculosis at just 34 years old.

“The Fly” was written in 1922, just a year before her death, and it’s deeply connected to her own experience of loss. Her beloved younger brother, Leslie, was killed in World War I in 1915, and his death devastated her. This story, written seven years after his death, explores how we deal with grief – or more accurately, how we fail to deal with grief.

The story was published during the aftermath of World War I, when Europe was still reeling from the massive loss of life. Nearly an entire generation of young men had been wiped out. So when we read this story, we need to keep in mind that Mansfield is writing for an audience who would have immediately understood the weight of mourning a lost son.

Plot Summary

Let’s get a quick overview of what happens in the story before we dive deeper. The text and audio of “The Fly” is available here.

The story revolves around three main characters:

The boss – an elderly businessman whose son was killed in the war six years ago

Mr. Woodifield – an old, retired man who visits the boss

The fly – yes, literally an insect, but symbolically much more

The story opens with old Mr. Woodifield visiting the boss in his office. Woodifield is described as frail and retired due to a stroke, only allowed out by his family once a week. The boss, in contrast, still runs his business and seems vigorous for his age. The boss shows off his refurbished office to Woodifield and offers him some whisky. After some small talk, Woodifield mentions that his daughters recently visited Belgium and saw the graves of the war dead – including the boss’s son’s grave. They remarked how well-kept the graves were. This mention catches the boss off-guard. After Woodifield leaves, the boss sits down, expecting to feel the usual overwhelming grief about his son’s death. But strangely, he can’t conjure up the feeling. He can’t even picture his son’s face clearly. While he’s struggling with this emotional numbness, he notices a fly that has fallen into his inkpot. He rescues it, watches it clean itself and recover, and then – in a disturbing turn – he deliberately drops more ink on the fly. He does this repeatedly, watching the fly struggle and recover each time, until finally the fly dies. The story ends with the boss feeling “wretched” and calling for fresh blotting paper, but when his assistant asks what was there before, the boss cannot remember. He has forgotten about the fly entirely.

Key Themes

Grief and the Passage of Time

The central question of this story is: What happens to grief over time?

The boss is shocked to discover that he can’t feel his grief anymore. Six years have passed since his son died, and he’s horrified to realize that time has somehow dulled the pain. There’s this devastating moment where he tries to weep – he wants to weep, expects to weep – but he can’t. Think about it like this: Have you ever had something terrible happen, and in the immediate aftermath, the pain is so raw and real that you think you’ll never stop feeling it? But then months or years pass, and one day you realize you went a whole day without thinking about it. And that realization itself can be painful – it feels like a betrayal, like you’re dishonoring the memory of what you lost. Mansfield is exploring this uncomfortable truth: grief fades, whether we want it to or not. And for someone like the boss, who has built his entire identity around being the grieving father, losing that grief means losing a part of himself.

Repressed Emotions and Psychological Denial

The boss can’t access his grief directly, so it comes out in a twisted, displaced way – through his torture of the fly. This is classic Freudian psychology (remember, Mansfield was writing at a time when Freud’s ideas were very influential). The boss has repressed his emotions so deeply that he can’t express them normally. Instead, they manifest in this cruel, unconscious behavior. It’s like when you’re really angry at someone but you can’t express it, so you end up snapping at someone else entirely – a friend, a family member, even a pet. The emotion has to go somewhere, and it finds an outlet in unexpected ways.

Power and Control

Throughout the story, there’s this theme of control and loss of control. The boss is clearly a man who likes to be in control. He runs a successful business, he’s refurbished his office beautifully, he offers Woodifield whisky from his private supply – he’s the one in charge. But his son’s death represents the ultimate loss of control. He couldn’t protect his son. He couldn’t stop the war. He couldn’t prevent the death. When he tortures the fly, he’s exercising control over life and death in a way he couldn’t with his son. He’s playing God, deciding when the fly lives and when it dies. It’s a twisted attempt to regain some sense of power over mortality.

Resilience and the Struggle to Survive

The fly becomes a symbol of resilience. Each time the boss drops ink on it, the fly struggles, cleans itself, and tries to survive. You could read this as the boss seeing his son in the fly – a young creature struggling against overwhelming forces, fighting to survive despite impossible odds. Each time the fly recovers, it’s like watching his son go off to war again, hoping this time he’ll make it through. But there’s also something darker here: the boss keeps testing the fly, keeps pushing it, until finally it can’t recover anymore. It’s as if he’s asking: How much can one endure before giving up? What’s the breaking point?

Memory and Forgetting

The ending is absolutely crucial. The boss forgets about the fly the moment his assistant removes it. He can’t even remember what was on the blotting paper just moments before. This is Mansfield’s most chilling insight: we forget everything eventually, even the things we swore we’d never forget. The boss was worried he couldn’t feel his grief anymore, but the ending suggests something even worse – we don’t just lose our feelings, we lose the memories themselves. It’s a terrifying thought. All those promises we make – “I’ll never forget you,” “I’ll always remember this” – are they lies we tell ourselves? Will time inevitably erase everything?

Symbolism and Literary Techniques

The Fly as Symbol

The fly is obviously the story’s central symbol, and it works on multiple levels:

The Son: Most obviously, the fly represents the boss’s dead son – a young life struggling against forces beyond its control, ultimately crushed by something much more powerful.

Humanity in War: More broadly, the fly represents all the young soldiers in WWI – millions of young men who were casually destroyed by forces (generals, governments, the machinery of war) that were indifferent to their individual lives.

The Boss Himself: There’s an argument to be made that the fly also represents the boss. He’s struggling against the inevitability of grief, death, and forgetting. Despite his efforts to maintain control, he too is being worn down by forces he can’t control.

Life’s Fragility: On the most universal level, the fly represents how fragile life is, and how easily it can be snuffed out by circumstances or by those with power over us.

The Ink

The ink is also symbolic. It’s black (like death), it’s suffocating (the fly drowns in it), and it comes from the boss’s work – suggesting that the demands of business, of moving forward, of “inking out” the past, are what’s drowning the boss’s ability to grieve. Also, ink is used for writing – for recording, for remembering. But here it’s used to kill and to blot out. It’s as if the very tool of memory is being turned into an instrument of forgetting.

The Office

The boss’s office has been completely refurbished. Everything is new and shiny. This renovation is significant – he’s literally covered up the old with the new, just as he’s tried to cover his grief with business and routine. The office is described as comfortable, warm, inviting – it’s a cocoon that protects the boss from having to face his emotions directly.

Woodifield as Foil

Old Woodifield serves as a mirror and contrast to the boss:

- Woodifield is visibly frail and has given up work; the boss appears vigorous and still works

- Woodifield is allowed out once a week; the boss seems free

- Woodifield has lost his power and agency; the boss still has his

But here’s the thing: despite appearances, the boss is just as much a prisoner as Woodifield. Woodifield is trapped by his physical weakness; the boss is trapped by his emotional repression. Neither man is truly free.

There’s also something significant about Woodifield being the one to bring up the son’s death. He does it casually, almost thoughtlessly, because for him it’s just a piece of information. But for the boss, it’s a bomb being dropped into his carefully constructed emotional defenses.

Writing Style and Narrative Technique

Mansfield’s style in this story is deceptively simple. The sentences are short and straightforward, the vocabulary is ordinary, and the plot seems basic. But look closer, and you’ll see how carefully crafted every element is.

Stream of Consciousness Elements

While not full stream-of-consciousness like Virginia Woolf or James Joyce, Mansfield does give us access to the boss’s thoughts in a way that feels natural and unfiltered. We follow his mental processes as he tries and fails to conjure up grief.

Irony

The story is drenched in irony:

- The boss prides himself on being strong, but he’s emotionally paralyzed

- He rescues the fly initially, but then tortures it

- He wants to remember his son, but ends up forgetting the fly completely

- He seems more alive than Woodifield, but emotionally he’s more dead

Free Indirect Discourse

Mansfield uses free indirect discourse brilliantly – we’re in the boss’s head, but we also have some distance from him. This lets us see his self-deception even as we understand his pain. We can be sympathetic to him while also being horrified by his actions.

The Ending

That ending is a masterclass in ambiguity and restraint. Mansfield doesn’t explain or moralize. She just shows us the boss forgetting, and leaves us to draw our own conclusions. It’s more powerful because of what it doesn’t say.

Close Reading of Key Passages

Let take a deeper look at a few crucial passages:

Opening Description of Woodifield

“Old Mr. Woodifield was still a pretty old man. But since his stroke, his wife and his girls had kept him boxed up in the house every day of the week except Tuesday.”

Note how Mansfield immediately establishes the theme of confinement and control. Woodifield is “boxed up” – like a corpse, like something preserved but not really alive.

The Boss Showing Off

“He rolled towards his writing-table and took up a leather-bound report and drummed on it with his pink, fleshy fingers. ‘I’ve got it all in here, my boy.'”

Everything here suggests vitality and control – rolling, drumming, pink, fleshy. The boss is showing himself as alive, capable, in command. But the very need to demonstrate this suggests its opposite.

The Moment of Emotional Blankness

“For the life of him he could not remember. All he knew was that he had been sitting there at his writing-table, with his hands over his face, trying to see his son, to get him clear. And the boy had been no more than that – a memory.”

This is the devastating moment where the boss realizes his grief has faded. The repetition of “trying” emphasizes the effort and the failure. The son has become “no more than a memory” – and even the memory is unclear.

The Torture Begins

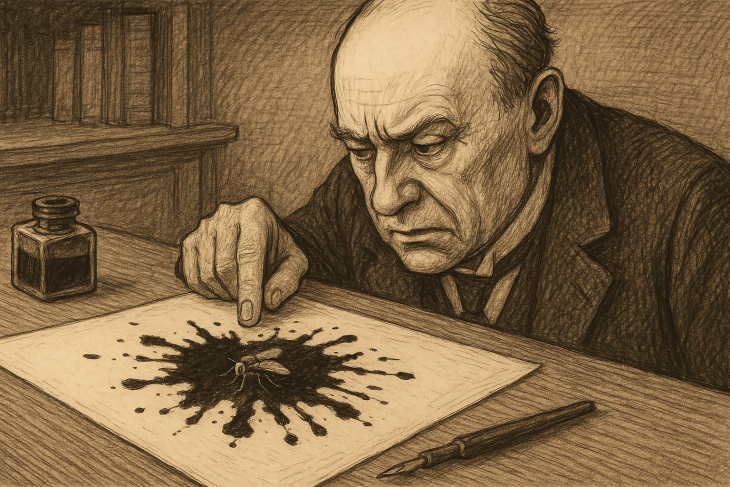

“He plunged his pen back into the ink, leaned his thick wrist on the blotting-paper, and as the fly tried its wings, down came a great heavy blot.”

Notice the violence in the verbs: “plunged,” “leaned,” “down came.” Also notice “great heavy blot” – it’s like a bomb dropping, crushing the fly’s attempt at recovery.

The Final Forgetting

“‘Bring me some fresh blotting-paper,’ he said sternly, ‘and look sharp about it.’ And while the old dog padded away he fell to wondering what it was he had been thinking about before. What was it? It was… He took out his handkerchief and passed it inside his collar. For the life of him he could not remember.”

The phrase “for the life of him” appears twice in the story – once when he can’t remember his son clearly, once when he can’t remember the fly. This repetition links the two forgettings and suggests they’re really the same thing.

Also notice: he wipes his collar, a gesture that suggests discomfort, guilt, or trying to clean away something unpleasant. And he never recovers the memory. The story ends with forgetting.

Historical and Biographical Context

World War I and the Lost Generation

To truly understand “The Fly,” we need to grasp the impact of World War I on British society.

WWI (1914-1918) killed approximately 17 million people, including about 886,000 British soldiers. But the numbers don’t capture the psychological impact. This was the first modern, mechanized war – men went “over the top” of trenches into machine gun fire, were blown apart by artillery, gassed, drowned in mud. It was slaughter on an industrial scale.

The phrase “the Lost Generation” refers to the massive number of young men who died. Entire communities lost almost all their young men. Britain was left with a generation of grieving parents, widows, and orphans.

Mansfield’s brother Leslie was one of these casualties. He was killed during a training exercise in 1915 (not even in battle, which makes it even more senseless). He was only 21. Katherine adored him – they had been very close as children in New Zealand.

After Leslie’s death, Katherine wrote: “I want to write about Leslie and make him live again.” But she couldn’t do it directly. Instead, grief permeates her work in indirect, displaced ways – like in “The Fly.”

Modernism and Psychological Realism

Mansfield was part of the Modernist movement in literature, which revolutionized how stories were told. Instead of clear plots with neat resolutions, Modernist writers focused on:

- Interior consciousness: What goes on inside people’s heads

- Ambiguity: Not providing clear answers or morals

- Everyday moments: Finding meaning in ordinary life rather than dramatic events

- Psychological realism: Showing how people really think and feel, including all the contradictions and unconscious motivations

“The Fly” is a perfect example of Modernist technique. Nothing much “happens” in terms of external plot – a man has a visitor, they chat, the visitor leaves, the man tortures a fly. But internally, psychologically, everything happens. We witness a man’s confrontation with loss, denial, displaced cruelty, and forgetting.

Freudian Psychology

Sigmund Freud’s ideas about the unconscious mind, repression, and displaced emotions were hugely influential in the early 20th century. Mansfield would have been familiar with these concepts.

The boss’s behavior can be read through a Freudian lens:

- He has repressed his grief (pushed it into the unconscious)

- It returns in disguised form (the torture of the fly)

- He can’t consciously acknowledge what he’s really doing

- His forgetting is a defense mechanism, protecting him from unbearable knowledge

Different Interpretations and Critical Perspectives

Psychoanalytic Reading

From this perspective, the boss is suffering from what Freud called “melancholia” – a pathological form of grief where the mourner’s anger at being abandoned by the deceased turns inward. But because he can’t express anger at his dead son, he displaces it onto the fly.

The fly torture is really a form of self-torture. The boss is punishing himself for failing to save his son, for forgetting his son, for moving on with life.

Feminist Reading

A feminist critic might point out that grief in this story is coded as masculine and repressed. The boss can’t cry, can’t express emotion openly – he has to maintain his strong, manly façade. This emotional repression is linked to patriarchal ideas about masculinity that are ultimately destructive.

Compare this to how women’s grief was treated in the period – women were expected to mourn openly, to wear black, to display their grief publicly. Men were expected to “soldier on” (a telling phrase!). The story critiques this gendered approach to grief.

Postcolonial Reading

The boss is described as having made his money and built his business, likely through colonial trade (this was the British Empire at its height). His son was fighting in a war that was essentially about imperial powers competing for global dominance.

From this angle, the fly represents the colonized – small, powerless creatures that the bosses of the world casually crush in their games of power. The boss’s inability to truly see or remember the fly mirrors imperial Britain’s inability to see the humanity of colonized peoples.

Moral/Ethical Reading

Some critics read the story as an indictment of the boss’s cruelty. He’s not just a victim of grief – he’s also a perpetrator of violence. The story asks us to think about how suffering can make us cruel rather than compassionate.

The boss had a choice about how to respond to his pain, and he chose (unconsciously) to inflict pain on something weaker. This is how cycles of violence perpetuate themselves.

Discussion Questions

Now that we’ve explored the story, let’s think about some questions to deepen our understanding:

- Is the boss aware of what he’s really doing when he tortures the fly? At what level of consciousness is this happening? Does he know on some level that the fly represents his son?

- Is forgetting a natural, inevitable process, or is it a form of betrayal? What does the story suggest about the ethics of moving on from grief?

- Is the boss a sympathetic character? Can we feel sorry for him while also being disturbed by his actions? How does Mansfield make us feel multiple, conflicting things about him?

- What does the story suggest about the relationship between grief and power? How are the boss’s attempts to control death related to his business and social power?

- Is there a “correct” way to grieve? The story seems to criticize both Woodifield’s casual mention of death and the boss’s repressed emotion. What would a healthy response look like?

- What is the significance of the story being set in an office rather than a home? How does the business setting contribute to the meaning?

- Why does Mansfield choose a fly rather than some other creature? What’s specific about a fly as a symbol?

- Can we read the story as being about Mansfield herself and her grief for her brother? How might this be a form of working through her own emotional paralysis?

- What does the story suggest about the aftermath of war on those who survive? Is this a war story, even though it’s set in a peaceful office?

- The boss is never named – he’s just “the boss.” What’s the effect of this choice? How does it make him more or less sympathetic?

Comparative Connections

To help you understand “The Fly” in a broader literary context, let me connect it to some other works you might know:

Other Stories About Grief

- “Miss Brill” by Katherine Mansfield (1920): Another Mansfield story about denial and the painful moment when self-delusion breaks down. Miss Brill creates a fantasy world to protect herself from loneliness, much as the boss has created emotional walls.

- “The Dead” by James Joyce (1914): The ending of Joyce’s story, where Gabriel realizes his wife has loved someone who died long ago, shares with “The Fly” this theme of how the dead continue to haunt the living and how we can never fully know others’ grief.

- “A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner (1930): Like the boss, Emily Grierson can’t let go of the dead, but she goes to even more extreme lengths. Both stories explore how grief can become twisted and destructive.

The Modernist Moment

“The Fly” shares characteristics with other modernist works that focus on internal consciousness and everyday epiphanies:

- Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway” (1925): Like Woolf, Mansfield takes us deep into a character’s consciousness and shows how seemingly ordinary moments contain profound psychological revelations.

- T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” (1922): Published the same year as “The Fly,” Eliot’s poem also deals with emotional numbness, death, and the struggle to feel authentic emotion in the modern world.

War Literature

As a response to WWI, “The Fly” can be read alongside:

- Wilfred Owen’s war poetry (1917-1918): Owen’s poems like “Dulce et Decorum Est” show the horror of war directly, while Mansfield shows its delayed psychological impact on those at home.

- Pat Barker’s “Regeneration Trilogy” (1990s): These novels explore the psychological trauma of WWI soldiers and the inadequacy of British emotional culture to deal with grief and trauma.

Mansfield’s Legacy

Katherine Mansfield died of tuberculosis in January 1923, just a few months after “The Fly” was published. She was only 34 years old. Despite her short life, she left behind some of the finest short stories in English literature.

Mansfield revolutionized the short story form. She showed that you didn’t need dramatic plots or clear resolutions. You could find profound meaning in the smallest moments – a woman trying on a hat, a man drowning a fly, a young girl experiencing her first ball.

Her influence on later writers has been enormous. Writers like Alice Munro, Mavis Gallant, and many others have acknowledged her as a pioneer who showed them what the short story could do.

“The Fly” in particular has become one of the most anthologized and studied short stories in English. It’s taught in universities around the world, written about by countless critics, and continues to move readers nearly a century after it was written.

Conclusion

So what makes “The Fly” such a powerful and enduring story?

I think it’s because Mansfield captures something fundamental about human psychology – the way we defend ourselves against unbearable knowledge, the way emotions find outlets in unexpected places, and the way time does things to our feelings that we can’t control.

The story is also ambiguous enough to reward multiple readings. Every time you come back to it, you might see something new. Is it about grief? Cruelty? Power? The passage of time? Repressed emotion? The answer is: yes, all of these things, and more.

And finally, there’s something about that ending – that moment of forgetting – that just haunts you. It’s so simple, so understated, but it captures something terrifying about human consciousness. We think we’re in control of our memories, our emotions, our identities. But are we really? What if everything we think is permanent is actually slipping away, all the time, and we don’t even notice?

Mansfield asks these questions without providing easy answers. And that’s what makes her a great writer. She trusts us, as readers, to sit with the discomfort, to think through the implications, to bring our own experiences of loss and memory to the story.

Final Thoughts

“The Fly” is only about 2,000 words long – you can read it in ten minutes. But those ten minutes contain depths that you can explore for hours, days, years. That’s the mark of great literature.

The next time you experience loss, or watch someone you love struggle with grief, or find yourself avoiding an emotion that’s too painful to face directly, you might think of this story. You might recognize something of the boss in yourself – not the cruelty, hopefully, but the human tendency to protect ourselves from what we can’t bear to feel.

And maybe that’s the ultimate value of literature: it shows us ourselves. Not in a mirror, exactly, but in a way that’s transformed, made symbolic, made bearable through art. Mansfield takes the raw wound of grief and transforms it into a story about a man and a fly. The transformation doesn’t make the pain less real – if anything, it makes it more universal, more shareable, more understandable.

That’s what great writers do. They take the chaos of human experience and shape it into something we can hold in our hands and examine. They give us language for things we thought were unspeakable. They show us we’re not alone.

And on that note, I’ll leave you with one final question to ponder: By the end of the story, has the boss learned anything? Or is he condemned to repeat this pattern – of approaching his grief, being unable to face it, displacing it onto something else, and then forgetting?

7 comments

Chicago residents can easily get their refrigerators fixed with the help of professional repair services available in the city.Looking for the services provided by subzerorepair247.com? Look no further!

Don’t lose hope if your sub zero wine cooler isn’t functioning correctly. It could simply require some repairs. However, it’s crucial to have them done quickly. Our company is a top repair service provider in Chicago and surrounding areas for sub zero wine cooler and storage repairs.

GE freezer repair service Chicago handled by authorized GE repair technician. We offer complete GE appliance repair Chicago including microwave, oven, washer, and refrigerator repairs with fast turnaround.

Best Appliance Repair Chicago is your trusted local expert for home and commercial appliance repair. We provide affordable same-day service for refrigerator, dishwasher, oven, and washer repair with certified technicians and 24-hour availability throughout Chicago.

I’ve been browsing on-line greater than 3 hours these days, but I never found any attention-grabbing article like yours. It is lovely value sufficient for me. In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made good content material as you did, the net will likely be much more useful than ever before. “Now I see the secret of the making of the best persons.” by Walt Whitman.

As a Newbie, I am always searching online for articles that can be of assistance to me. Thank you

**mitolyn official**

Mitolyn is a carefully developed, plant-based formula created to help support metabolic efficiency and encourage healthy, lasting weight management.